When an Xcode build fails, developers instinctively reach for logs. We scroll through walls of text, searching for that one cryptic linker error or mysterious crash buried in the noise. The build system knows exactly what happened (every compilation, every dependency resolution, every timing metric) but it speaks a language optimized for machines, not humans. And certainly not for AI agents.

What if we could change that? What if AI agents could actually understand builds, not just parse their text output?

This is an exploration of what could be possible. Some of the concepts discussed are aspirational and would require Apple's support to fully realize.

The Problem: Build Logs Are Not Built for Understanding

Picture this: you're building a large iOS app and hit a linker error. The output looks something like this:

What do you do next? You scroll up through hundreds of lines of compilation output, grep for "error", check if your Swift Package dependencies resolved correctly, maybe clean the build folder, and try again. If that doesn't work, you might delete the DerivedData folder entirely and rebuild from scratch. Sometimes that fixes things. Sometimes it doesn't, and you're left wondering what actually went wrong.

The frustrating part is that the build system knows exactly what happened. It knows which target failed, which dependency was missing, what the entire dependency graph looks like, and how long each step took. But instead of exposing this rich structured data, it communicates through a stream of text that looks like it was designed for a terminal from the 1980s.

We've all been there. We've all lost hours to build failures that should have taken minutes to diagnose.

What xcodebuild actually gives you

When you run xcodebuild from the command line, you get output that mixes progress indicators, compiler invocations, warnings, and errors into a single undifferentiated stream:

This output wasn't designed for debugging. It was designed for logging. There's no structure, no hierarchy, no way to programmatically distinguish between a compilation step and a linker invocation without parsing the text itself.

For humans, tools like xcbeautify help by colorizing the output and filtering out noise. They make the wall of text easier to scan. But these tools are designed for human eyes scanning a terminal. They take unstructured text and make it prettier unstructured text.

Why this matters for AI agents

Now consider what happens when an AI agent tries to help you debug a build failure. The agent faces a fundamental challenge: the output it receives is unstructured text. It has to parse free-form strings, try to guess at relationships between different lines, and hope that the error message contains enough context to be useful.

Even with perfect parsing (which is hard, because the output format isn't formally specified and can change between Xcode versions), there's critical information that simply isn't present in the logs. None of this information appears in xcodebuild output. It exists inside the build system, but it doesn't make it to the terminal.

A step in the right direction: xcsift

There's an interesting project called xcsift that takes a different approach to this problem. Instead of formatting build output for humans to read, it transforms xcodebuild output into structured JSON that's optimized for AI consumption:

This produces machine-readable output with extracted errors, warnings, and test failures organized into a proper data structure. The tool even offers a custom format called "TOON" that reduces token usage by 30-60% compared to JSON, which matters when you're paying per token for AI API calls.

This is a genuinely clever solution. It works within the constraints of what xcodebuild exposes and makes the best of a difficult situation.

But there's a fundamental limitation: xcodebuild output is a flattened representation of what's actually happening. The build system internally maintains a rich graph of dependencies (target A depends on target B, file X imports module Y, this compilation must wait for that linking step). When it writes to stdout, all of that structure gets serialized into a linear stream of text. The graph becomes a list. The relationships disappear.

xcsift can parse that list beautifully, but it can't reconstruct the graph. It can tell you that target A failed, but not that targets B, C, and D were waiting on A and never got a chance to run. It can tell you that a file was compiled, but not why it needed recompilation or what downstream tasks were triggered as a result.

The build system has this information. It just doesn't share it.

The gap between parsing logs and observing builds

There's a meaningful difference between parsing build logs and actually observing what the build system is doing. It's a bit like the difference between reading a transcript of a meeting and actually being in the room. The transcript captures the words that were spoken, but it loses the timing, the context, the reactions, the side conversations.

When you parse xcodebuild output, you're working with what the build system chose to print. When you observe the build system's internal messages, you see everything: every task that started and ended, every dependency that was resolved, every timing measurement, every decision the scheduler made.

That's what we wanted to explore. What if instead of parsing the output of xcodebuild, we could tap into the structured messages that the build system uses internally to coordinate its work? What would that unlock for AI agents trying to understand and debug builds?

Discovering What Builds Actually Know

A few months ago, we got curious. We built a small tool called XCBLoggingBuildService to intercept the communication between Xcode and its build service. We wanted to see what was actually happening under the hood.

What we found changed how we think about build observability.

When you hit "Build" in Xcode or run xcodebuild, you're not directly invoking compilers and linkers. Your request goes to a separate process called SWBBuildService. This is the actual build engine. Xcode is just a frontend that sends requests, receives responses, and translates them into the UI you see. The same goes for xcodebuild, which translates them into text.

The communication between these processes isn't text. It's not JSON either. It's MessagePack, a binary serialization format, flowing over stdin/stdout pipes. And here's the thing: every build event is a discrete, typed message with structured data.

Apple recently open-sourced this build system as swift-build. So now we can actually read the message definitions. We can see exactly what data flows between components. What was once a black box is now source code anyone can study.

The difference is striking

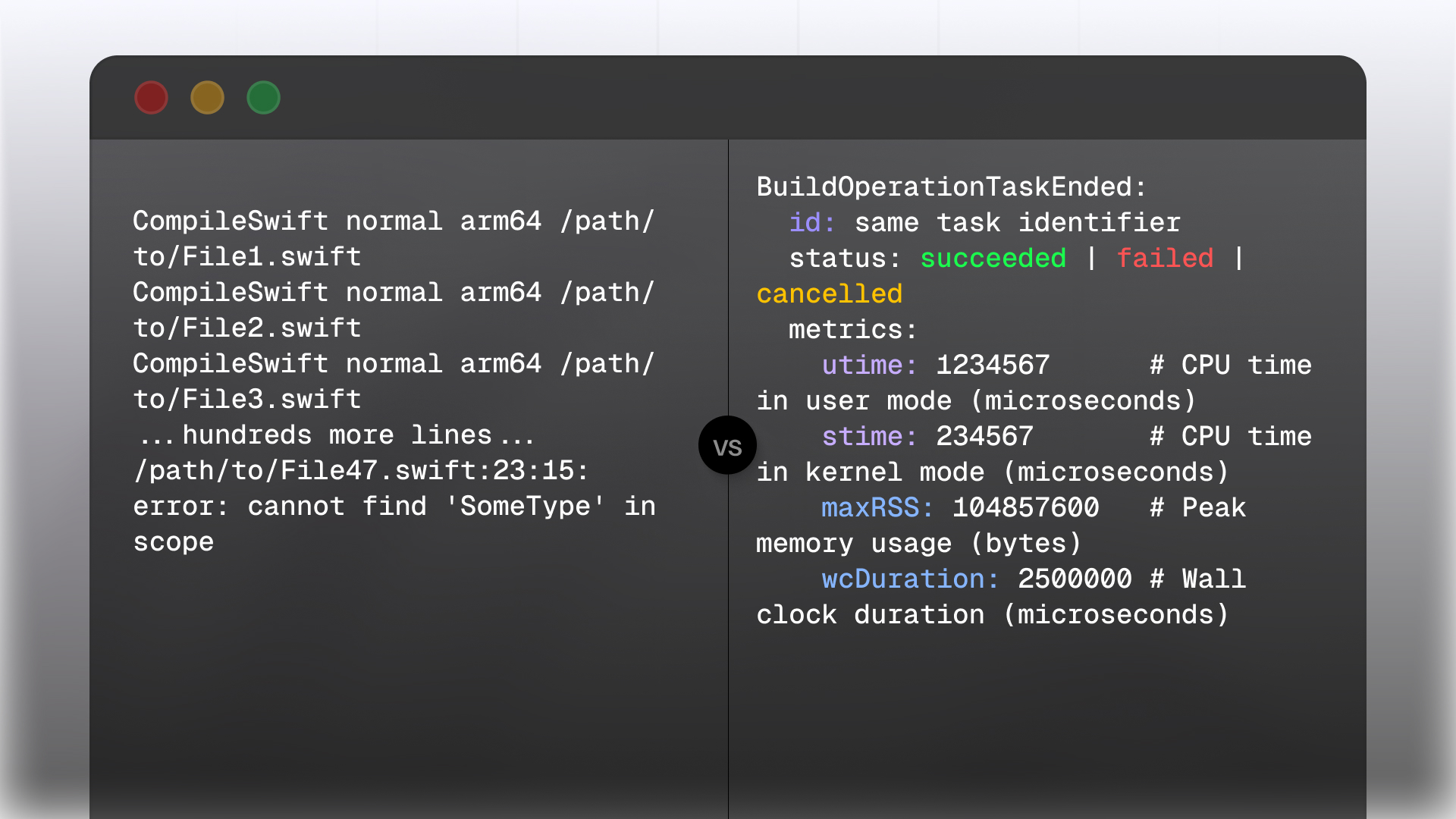

Let's look at a concrete example. When you compile a Swift file, xcodebuild prints this:

One line. That's it.

But internally, the build service sends a BuildOperationTaskStarted message that looks like this:

And when that compilation finishes, there's a BuildOperationTaskEnded message:

See the difference? The protocol knows how long the compilation took, how much memory it used, which target it belonged to, and whether it was part of a larger task. It has a unique identifier that lets you correlate this task with any errors it produced, any output it generated, and its position in the dependency graph.

None of that makes it to the terminal.

What gets lost in translation

When we started looking at the SWBProtocol module, we kept finding data that never reaches xcodebuild output:

Timing, for one. Not just "the build took 45 seconds," but exactly how long each individual task took. You can see that a compilation ate 8 seconds of wall time but only 2 seconds of CPU time, which tells you it was probably blocked waiting for something else.

Memory usage per task. If your CI builds are getting killed by the OOM killer, you could pinpoint exactly which compilation is the culprit.

Task relationships. Every task knows which target it belongs to, and optionally which parent task spawned it. You can reconstruct the full tree of what happened, not just a flat list.

Cache information. There's a message called BuildOperationTaskUpToDate that fires when a task was skipped because nothing changed. You could calculate your actual cache hit rate instead of guessing.

And diagnostics. Errors don't come as text strings. They come as BuildOperationDiagnosticEmitted messages with the file path, line and column, source ranges, fix-it suggestions, and which component emitted them.

The build system knows all of this. It's just not telling us.

What Structured Build Data Unlocks

So we have this rich stream of structured messages flowing through the build system. What could we actually do with it if we captured and exposed it properly?

Intelligent failure diagnosis

When a build fails today, an AI agent sees an error message and tries to help based on pattern matching against its training data. Sometimes that works. Often it doesn't, because the agent lacks context about your specific project.

With structured build data, the agent could answer questions like:

-

"This linker error happened because target

NetworkKitfailed to build.NetworkKitdepends onCoreUtilities, which succeeded, so the problem is isolated toNetworkKititself." - "You've seen this exact error three times in the last week. The first two times, cleaning the build folder fixed it. The third time, you had to delete DerivedData."

-

"This compilation failed at 2:34 PM. The last successful build was at 2:12 PM. Between those builds, you modified

APIClient.swiftandModels/User.swift."

The agent isn't guessing anymore. It's working with actual build history and dependency information.

Performance analysis that goes beyond timing

Build performance is usually measured in one number: how long did it take? But that number hides a lot of complexity. A 60-second build might be 60 seconds because you have one massive target that can't parallelize, or because you have 30 small targets with a long critical path, or because your incremental build isn't actually incremental.

With task-level timing and dependency data, you can answer the questions that actually matter:

- "Your build took 47 seconds, but only 12 seconds of that was actual compilation. The rest was waiting for code signing and asset catalog processing, which ran sequentially after everything else."

-

"The critical path runs through

FeatureA→SharedUI→MainApp. If you could shave 5 seconds offSharedUI, your entire build would be 5 seconds faster." - "You have 8 CPU cores, but your build only achieved 3.2x parallelization. Here are the targets that are blocking better parallelization."

-

"This 'incremental' build recompiled 847 files. Based on the task signatures, the trigger was a change to

Constants.swift, which is imported by everything."

The data includes start and end times for every task, plus which target each task belongs to. From this, you can compute concurrency over time, identify sequential chains (likely dependencies), find the critical path, and spot contention points where one target blocks many others.

For example, if tasks from target A consistently end right before tasks from targets B, C, and D begin, target A is probably a dependency of all three. If A takes 20 seconds and blocks everything else, that's your bottleneck. The protocol also includes a DependencyGraphResponse message with an explicit adjacency list of target dependencies, so you can get the actual dependency graph, not just inferred relationships from timing.

This is the kind of analysis that build engineers at large companies do manually, staring at build traces and dependency graphs. There's no reason an AI agent couldn't do it automatically if it had access to the same data.

Proactive suggestions

Once you have historical build data, patterns start to emerge. An agent with access to weeks or months of build history could notice things like:

-

"Your clean build times have increased by 40% over the last month. The growth correlates with the addition of 12 new Swift files in the

Analyticsmodule." - "Builds on Monday mornings are consistently 2x slower than other times. This might be related to cache invalidation over the weekend."

- "Developer A's builds fail 3x more often than Developer B's, and the failures are almost always linker errors. This might indicate an environment configuration issue."

- "This target has been rebuilt from scratch in 80% of incremental builds. The problem appears to be a bridging header that changes frequently."

None of this is possible with a single build's text output. It requires structured data that can be stored, queried, and compared over time.

Natural language queries about builds

Perhaps the most immediately useful application is simply being able to ask questions about your builds in plain English:

- "What was the slowest target in my last build?"

- "How many warnings did we have last week compared to this week?"

- "Which files take the longest to compile?"

- "Has this test target always been this slow, or did something change recently?"

- "What percentage of my builds are clean builds versus incremental?"

These questions have answers. The build system knows the answers. We just don't have a good way to ask.

Why this matters now

AI agents are becoming legitimate development tools. People use them to write code, debug issues, refactor systems, and automate workflows. But when it comes to builds, agents are working blind. They can see the code, but they can't see how the code gets built.

As projects get larger and build systems get more complex, this gap becomes more painful. A developer might spend hours debugging a build issue that an agent could diagnose in seconds, if only the agent had access to the right data.

The structured messages are already there. The build system already generates them. The question is whether we can capture them in a way that makes them accessible to the tools developers are increasingly relying on.

Inside the Build Protocol

So where does this build service actually live? If you dig into your Xcode installation, you'll find it here:

That's the binary that does all the work. When you build something, Xcode spawns this as a separate process and talks to it over stdin/stdout pipes. Looking at BuildServiceEntryPoint.swift in swift-build, you can see it also supports running in-process, which is probably how Xcode uses it for tighter integration.

How Xcode understands your project

Before a build can start, the build service needs to understand your project structure. This happens through something called PIF: the Project Interchange Format.

If you've ever tried to parse an .xcodeproj file programmatically, you know it's a nightmare. The .pbxproj format is byzantine, poorly documented, and full of UUIDs that reference each other in ways that are hard to follow. PIF is what the build system actually uses internally, and it's much cleaner.

Looking at the ProjectModel directory in swift-build, you can see the hierarchy: workspaces contain projects, projects contain targets, targets contain build phases, and build phases contain files. It's all defined in straightforward Swift structs like Workspace.swift, Project.swift, and Target.swift.

What's clever is that PIF supports incremental updates. The build service caches your project structure, and on subsequent builds, only the parts that changed get re-transferred. That's part of why incremental builds in Xcode feel faster than running xcodebuild from scratch each time.

What happens during a build

When you actually kick off a build, there's a conversation that happens between Xcode and the build service. First, Xcode establishes a session. Then it transfers the project structure (or updates to it). Then it sends a build request with the configuration, scheme, and targets.

During execution, the messages we talked about earlier start flowing: targets starting and ending, tasks starting and ending, progress updates, diagnostics. When everything's done, there's a final message with the overall status and aggregate metrics.

The interesting thing is that sessions can be reused. Xcode doesn't tear down the connection after each build. It keeps the session alive so that subsequent builds can skip the setup phase and benefit from cached state.

You can swap out the build service

Here's what makes this really interesting for observability: Xcode explicitly supports using a custom build service.

There's an environment variable called XCBBUILDSERVICE_PATH. If you set it, Xcode will use whatever binary you point to instead of the bundled one. The swift-build repository even includes a launch-xcode plugin that builds swift-build from source and launches Xcode with the custom service:

This means you could modify the build service, add logging for the messages you care about, rebuild it, and have Xcode use your version. Or you could build a proxy that sits between Xcode and the real build service, capturing messages as they flow through.

That's exactly what XCBLoggingBuildService does. It's a pass-through proxy that logs messages without modifying them:

The protocol isn't hidden. It's open source, documented in code, and Xcode explicitly supports swapping out the implementation. The pieces are all there for anyone who wants to build better observability into their build process.

Making Builds Agent-Friendly

Capturing build messages is only half the problem. The other half is making that data useful for AI agents.

If you just dump raw protocol messages into an agent's context, you'll quickly run into limits. A single build can generate thousands of messages. That's way too much for any reasonable context window, and most of it isn't relevant to whatever question you're trying to answer.

We need to think about this differently. Instead of giving agents raw data, we need to give them the right data at the right level of detail.

The correlation problem

There's a practical challenge we hit immediately: how do you connect a build invocation to its data?

When an agent runs xcodebuild, it needs some way to later ask "what happened in that build?" The build service doesn't automatically tag its output with any kind of identifier. If you're running multiple builds, or if you want to query historical data, you need a way to correlate them.

One approach is to pass a build ID through an environment variable. The agent generates a unique ID before invoking the build:

The logging service reads BUILD_TRACE_ID from the environment and tags all captured messages with it. Later, the agent can query using that same ID.

This sounds simple, but it's the kind of glue that makes the difference between a demo and something actually usable. Without correlation, you're stuck with "show me the last build" and hoping there wasn't a concurrent build that interleaved with it.

Storing build data

Where would you put all these messages? SQLite seems like a natural fit.

It might seem like overkill, but SQLite has some nice properties for this use case. It's a single file, so there's nothing to set up. It's queryable, so agents can ask specific questions without loading everything into memory. And it's portable, so you can copy build history between machines or share it with teammates.

The key insight is that you wouldn't want to store raw messages and query them directly. You'd want to pre-compute the things agents are likely to ask about. Think of it as layers:

Summary layer. One row per build with pre-computed metrics: total duration, number of targets, number of tasks, error count, warning count, cache hit rate, whether it succeeded or failed. This is maybe 50 tokens. An agent can get a high-level view of any build almost for free.

Top-N layer. The slowest targets, the slowest tasks, the most recent errors. Pre-sorted and limited. If an agent asks "why was this build slow?", you can answer with a couple hundred tokens instead of dumping the entire task list.

Details layer. Individual diagnostics, task timing breakdowns, the full error messages with file locations. You only fetch this when drilling down into something specific.

Raw layer. The original messages, stored as JSON. Almost never accessed, but there if you need to debug something weird or answer a question the other layers don't cover.

The schema might look something like this:

Nothing fancy. The point is to make common queries fast and cheap.

Exposing data to agents

Once you have the data stored, how do agents access it?

The simplest approach is a CLI. Agents can already execute shell commands, so there's no need for a separate server or protocol. A CLI built into the same executable that captures the data could expose commands like:

The agent just calls the command and gets back structured output. No server to run, no protocol to implement. The CLI handles the database queries and returns JSON or human-readable output depending on what's needed.

You could support convenient aliases too. Instead of requiring exact build IDs, let agents say latest for the most recent build, latest:MyScheme for the most recent build of a specific scheme, or failed for the most recent failure.

Real Build Analysis: Wikipedia iOS

To validate this approach, we instrumented a real build of the Wikipedia iOS app, a large open-source project with 19 targets and thousands of tasks. Here's what the build service captured:

Build Summary

A clean build completed in 457 seconds, spanning 19 targets and 3,303 individual tasks. Zero cache hits because we started fresh. The build succeeded with 86 warnings that would be worth investigating.

Identifying Bottlenecks

This is where the dependency graph becomes invaluable. By analyzing which targets block other targets and how long they take, we can compute a "bottleneck score" (duration x dependent count).

The WMF framework is the critical bottleneck. It takes 246 seconds and blocks 4 other targets from starting: ContinueReadingWidget, Wikipedia, WidgetsExtension, and NotificationServiceExtension. The app extensions all depend on it. If you wanted to improve build times, this is where to focus: either splitting WMF into smaller, more independent modules, or finding ways to parallelize work within it.

Other notable bottlenecks include CocoaLumberjack (34s, blocking 3 targets) and the individual app extensions (each around 252s, blocking the main Wikipedia target).

The Critical Path

Using the dependency graph, we can compute the longest chain of dependencies that determines the minimum possible build time: WMF (246s) -> ContinueReadingWidget (253s) -> Wikipedia (456s), totaling 955 seconds of serial work.

This tells us something important: if these targets ran sequentially, the build would take 955 seconds. The actual build took 457 seconds, meaning we achieved roughly 2.1x speedup through parallelization. But we can also see the limit: no amount of parallelization can make this build faster than whatever is on the critical path.

Slowest Targets

The five slowest targets tell an interesting story: Wikipedia (456s, 926 tasks), ContinueReadingWidget (253s, 61 tasks), WidgetsExtension (252s, 95 tasks), NotificationServiceExtension (252s, 60 tasks), and WMF (246s, 902 tasks).

Notice that ContinueReadingWidget takes 253 seconds but only has 61 tasks, while WMF has 902 tasks but takes slightly less time. This suggests the widget's compilation is CPU-bound on a few expensive files, while WMF has better internal parallelization.

Slowest Tasks

Drilling into individual tasks reveals optimization opportunities. Asset catalog compilation was the slowest single task at 131 seconds, using 3.1 MB of memory. This is nearly a third of the critical path target's time, and it runs as a single task that can't be parallelized.

The next slowest was a batch Swift compilation (83 seconds, 373.7 MB) covering 25 files including ArticleURLListViewController.swift and DonateFunnel.swift. Individual Swift file compilations showed similar times around 81 seconds because they're compiled together in the batch.

What an Agent Could Do With This

Armed with this data, an AI agent could provide actionable recommendations:

"Your Wikipedia iOS build took 457 seconds. The main bottleneck is the

WMFframework (246s), which blocks 4 other targets. Consider:

Split WMF: The framework has 902 build tasks. Breaking it into 2-3 smaller frameworks could allow better parallelization.

Asset catalog optimization: Asset catalog compilation takes 131 seconds and runs serially. Consider breaking the catalog into smaller, per-feature catalogs that can compile in parallel.

Build order insight: Your critical path is WMF -> ContinueReadingWidget -> Wikipedia. The theoretical minimum build time with infinite parallelization is 955 seconds serial time, you're achieving 2.1x parallelization.

86 warnings to fix: These don't affect build time, but fixing them will reduce noise and potential future issues."

This isn't guessing based on log output. It's analysis based on actual dependency relationships, task timing, and resource metrics that the build system tracks internally.

What This Requires

This exploration demonstrates what's possible, but turning it into a robust tool requires acknowledging some challenges.

Protocol Stability

The swift-build protocol is now open source, which is a significant step forward. What would make this truly useful is Apple officializing it: giving xcodebuild a flag to specify where to store build trace data (a SQLite database path), and providing a CLI interface to query that data. We've built exactly this in our exploration, and Apple could do the same with proper support. They'd need to standardize the data schema and handle migrations when the schema evolves across Xcode versions.

What's already possible with post-build artifacts

Before diving into what protocol-level access would unlock, it's worth recognizing what's already achievable today. Xcode generates .xcactivitylog files (gzip-compressed build logs with structured data) and .xcresultbundle directories (containing test results, code coverage, and build metadata). These artifacts contain a wealth of information that tools can parse after builds complete.

Tools like xclogparser have been parsing these files for years, extracting timing data, warnings, and errors into queryable formats. This post-hoc approach works well for many use cases: you can analyze build performance, track warning trends over time, and identify slow compilation units.

At Tuist, we've built exactly this. Our Build Insights feature parses .xcactivitylog and .xcresultbundle files to provide teams with dashboards showing build times, cache effectiveness, and historical trends. The data spans across developers, CI pipelines, and time, giving teams visibility into patterns they'd never notice from individual builds. And we're extending this to tests too: Test Insights (already available in our public dashboard) will bring the same cross-time, cross-space analysis to your test suite. Adopting it is as simple as adding a post-action to your Xcode schemes.

This matters because much of what we've described in the "Vision" section, like team-wide build intelligence and build archaeology, is achievable with post-build artifacts. You don't need Apple to bless a new extension point to start getting value from structured build data.

Why protocol-level access would still matter

So if we can already parse .xcactivitylog files, why bother with the build protocol at all?

The key differences come down to timing and data availability.

Real-time intervention. When you parse post-build artifacts, the build is already done. An AI agent watching the protocol stream could notice a problem mid-build and take action: pause the build, alert the developer, or even suggest a fix while there's still time to act on it. With post-hoc parsing, you're always reacting to something that already happened.

Rebuild causality. The protocol includes BuildOperationBacktraceFrameEmitted messages that explain why each task was rebuilt: was it because the rule never ran before? Because the signature changed? Because an input was rebuilt? This causal chain is invaluable for debugging incremental build issues, but it's ephemeral. It flows through the protocol during planning and execution, then disappears. Result bundles record that a task ran, but not the decision tree that led to it running.

Live dependency graph computation. The protocol exposes ComputeDependencyGraphRequest and ComputeDependencyGraphResponse messages showing how dependencies are resolved during planning. You can see the actual adjacency lists of target-to-target dependencies as the build system computes them. This information exists in the protocol as it happens, but the result bundle only contains the final build output, not the planning decisions.

Real-time progress. BuildOperationProgressUpdated messages stream live status with target names, status messages, and completion percentages. You could build a web dashboard showing your build's progress in real-time, with tasks appearing and completing as they happen. This enables experiences like watching your CI build live from anywhere, something that's not possible with post-hoc parsing.

Per-task resource attribution. While result bundles contain aggregate timing data, the protocol streams per-task metrics as each task completes: user-mode CPU time, system CPU time, peak memory usage, and wall-clock duration. This granularity makes it possible to identify not just which targets are slow, but which specific compilation units within those targets are consuming resources.

What would make this better

If Apple designed an extensible architecture where anyone can hook into the build event stream, the community could build powerful tooling on top of it. A stable contract for build events would enable real-time build monitoring in CI dashboards, AI agents that can intervene during builds, and custom workflows we haven't imagined yet.

The pieces are already there in swift-build. What's missing is Apple blessing this as an official extension point rather than an implementation detail that might change without notice.

The Vision: Where This Could Go

The Wikipedia iOS analysis shows what's possible with a single build. But the real potential emerges when you think about builds over time.

Much of what follows is achievable today by parsing .xcactivitylog and .xcresultbundle files after builds complete. That's exactly what we're building at Tuist with Build Insights. Protocol-level access would add real-time capabilities and richer causality data, but you don't need to wait for Apple to start getting value from structured build observability.

Team-Wide Build Intelligence

Imagine a CI system that captures structured build data from every pull request. Over weeks and months, patterns emerge:

- Which targets get slower as the codebase grows

- Which developers' changes tend to invalidate more cache entries

- What times of day have the slowest builds (and why)

- How merge queue builds differ from individual PR builds

This isn't theoretical, it's the kind of analysis that large companies do manually with custom tooling. Structured build data makes it accessible to everyone. And it's achievable today: post-build artifacts contain all the timing data, target information, and warning counts you need to build these dashboards.

Proactive Developer Assistance

With historical data and dependency information, agents could provide guidance before you even start a build:

"You're about to modify

Constants.swift. Based on build history, this file is imported by 847 other files and will trigger a near-clean rebuild. Would you like me to suggest a more targeted approach?"

Or during code review:

"This PR adds a new import to

SharedFramework.h. Our build data shows this header is included by 12 targets. This change will add approximately 45 seconds to incremental builds for those targets."

These insights come from correlating build data over time with code changes. The build artifacts contain timing data; the git history contains what changed. An AI agent with access to both can make these connections.

Real-Time Build Monitoring

This is where protocol-level access becomes essential. The build service generates events in real time, and an agent could watch these events as they happen:

"Build in progress... The

Analyticstarget is taking longer than usual (45s vs. typical 30s). This started after yesterday's PR that added 3 new tracking events. The additional compile time is coming from type inference inEventBuilder.swift."

Post-hoc parsing can tell you that Analytics was slow after the fact. Protocol-level access could tell you while it's happening, giving you the option to stop the build, investigate, or take corrective action before wasting more CI minutes.

Build Archaeology

When something goes wrong weeks later, structured data lets you investigate:

"This linker error started appearing 3 days ago. Looking at build history, the last successful build was commit

abc123. Between then and the first failure, there were 7 commits. The failure correlates with the addition ofNewFeature.frameworkwithout updating the library search paths."

This kind of analysis is entirely achievable with post-build artifacts. You need a database of historical builds with their errors, timing, and associated commits. Then it's a matter of querying and correlation, exactly what AI agents excel at.

The build system already knows everything it needs to answer these questions. The data is available in post-build artifacts. We just need to capture and expose it in a way that's useful.

Key Learnings

Building this exploration taught us several things:

The build system is far more sophisticated than it appears. What looks like "compile a bunch of files" is actually a complex graph scheduler with caching, parallelization, and detailed instrumentation. The data is there, it's just not exposed.

Structured data fundamentally changes what AI can do. An agent parsing "CompileSwift normal arm64..." has almost nothing to work with. The same agent given structured events with timing, dependencies, and metrics can provide genuinely useful analysis.

Context window efficiency matters. You can't dump 3000 build tasks into a prompt. The tiered approach (summary -> top-N -> details -> raw) makes the difference between "unusable" and "practical."

Dependency graphs are the key to build optimization. Knowing that WMF blocks 4 targets is far more actionable than knowing WMF takes 246 seconds. The graph tells you what to fix; timing alone just tells you something is slow.

Build observability is underinvested. Developers lose hours to build issues that could be diagnosed in minutes with better tooling. The gap between "what the build system knows" and "what developers can see" is enormous.

What's Next

There are two parallel paths forward, and we're actively working on both.

What you can use today

At Tuist, we're building Build Insights and Test Insights using post-build artifacts. This works today, requires no experimental tooling, and gives teams visibility into build performance across developers, CI pipelines, and time. Adopting it is as simple as adding a post-action to your Xcode schemes that uploads your .xcactivitylog and .xcresultbundle files.

This is the pragmatic path: you don't need Apple to bless anything, you don't need to swap out your build service, and you can start getting value immediately. Team-wide build intelligence, historical trends, warning tracking, and build archaeology are all achievable with post-build parsing.

Exploring real-time protocol access

For real-time features and richer causality data, we've open-sourced Argus, a fork of swift-build that provides an agentic interface for AI agents. This is very much an experiment. It demonstrates what's possible when you tap into the build event stream directly, including features that post-hoc parsing cannot provide:

- Real-time monitoring: Watch your build progress live in a dashboard

- Mid-build intervention: An agent could pause a build when it detects a problem

- Rebuild causality: Understand why tasks were rebuilt, not just that they were

- Live dependency resolution: See how the build system computes dependencies during planning

Install Argus globally using mise:

Then add the following to your agent's memory or system prompt to enable build observability:

If you have ideas for how to improve things, open PRs or issues on the Argus repository. We'd love to see what you build with it, so share your learnings on Mastodon, Bluesky, or LinkedIn and tag us.

Check out the swift-build repository to see the protocol definitions, join the Tuist community to discuss build optimization, or book a call if you need help scaling your development workflows.